As if Yemen Needed More Woes, a Decrepit Oil Tanker Threatens Disaster

A rusting vessel used for years to store oil off Yemen’s coast poses what the United Nations has called a dire and entirely preventable threat of ecological catastrophe.

Think of Yemen, and war, starvation, disease and poverty come to mind. Now add another attribute: a rusting, neglected 1,188-foot tanker moored off the country’s western coast, laden with roughly 48 million gallons of oil, at risk of sinking or even exploding at any time.

The United Nations and a variety of environmental experts have warned for years that the vessel, the FSO Safer, is like a floating bomb, one that could cause an ecological crisis with any leak in one of its 34 storage tanks. Together, they hold four times the amount of oil spilled in the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster.

A spill could further upend the lives of Yemen’s 28 million people, kill untold populations of fish and birds, poison coral reefs, gum up desalination plants and close the Red Sea shipping lanes and ports that are Yemen’s sole lifeline for international aid.

The Safer’s rusting hull and corroding pipes and valves are not the only worries. It is not far from Hudaydah, a hotly contested port city, and the risks of a stray shell or bomb striking the vessel cannot be ruled out.

“Should the situation get out of control, it will directly affect millions of people in a country that is already enduring the world’s largest humanitarian emergency,” Inger Anderson, the executive director of the United Nations Environment Program, told the Security Council on Wednesday in a briefing about the tanker problem. “It will destroy entire ecosystems for decades and go beyond borders.”

Prevention of either a spill or explosion aboard the Safer, Ms. Anderson said, “is really the only option to avoid an environmental and human catastrophe.”

The vessel, which requires extensive upkeep, has not been properly maintained since war broke out more than five years ago between the Houthi rebels and a Saudi-led military coalition that has been trying to crush them.

The Yemeni oil company that owns the Safer says it does not have the resources to service the vessel, which historically has functioned as a floating storage facility fed by the Marib-Ras Isa pipeline, which carries oil from eastern Yemen. A skeletal crew remains aboard, but much of the machinery used to prevent combustible buildups of gas in the tanks no longer operates.

The Houthis, who control the region that surrounds the mooring area, have long balked at United Nations requests to assess the vessel’s condition. But they appeared to have a change of heart after a seawater leak into the Safer’s engine room in May, which the crew and an emergency team of divers sent by the vessel’s owner were able to temporarily patch.

Speaking at the same Security Council briefing as Ms. Anderson, Mark Lowcock, the top relief official at the United Nations, said that the Houthi leadership had confirmed in writing that it would allow a long-planned U.N. mission to appraise the tanker, “which we hope will take place within the next few weeks.”

Still, Mr. Lowcock was guarded in his optimism. In August of 2019, the Houthis consented to a United Nations request to inspect the tanker, only to cancel it the night before.

The Houthis’ reluctance to relinquish control over the vessel stems in part from the group’s desire to sell the oil, or at least to use it for bargaining leverage with their Saudi adversaries. But the coronavirus pandemic has severely reduced the price of oil, making the Safer’s contents much less valuable. Moreover, the oil has been languishing in rusting tanks for at least five years, which may have befouled it.

“The Houthis may think, ‘We need to get rid of this before this becomes a massive problem for us,’” said Samir Madani, co-founder of TankerTrackers.com, an online service that monitors maritime shipments and storage of petroleum. “I would like to think that is the case.”

Moreover, he said, the Safer’s cargo “is probably contaminated — this would be the last deposit of oil you would want to buy.”

Ian M. Ralby, the founder and chief executive of I.R. Consilium, a maritime security consultancy, said it was possible that Houthi leaders who once viewed the Safer as an asset “may now see the benefit in allowing the situation to be resolved.”

If there were an oil disaster, he said, “the fallout would rest on their heads, and they can’t afford the permanent black mark, having negative and fatal implications.”

Other environmental and maritime shipping experts who have been keeping track of the Safer say there is no simple fix. The best hope, some said, is that once the U.N. inspectors can appraise the vessel’s condition, a salvage team will be permitted to siphon the oil out of its tanks into other vessels, then tow the Safer to a secure port for scrapping.

How that can be done in the midst of a war zone, further complicated by the coronavirus pandemic, constitutes another underlying challenge.

RIYADH — United Nations Secretary‑General António Guterres has described recent developments in Yemen’s Hadramout governorate as…

SANAA — Yemen’s Houthi movement has denounced United Nations Secretary‑General António Guterres, accusing him of meddling in the…

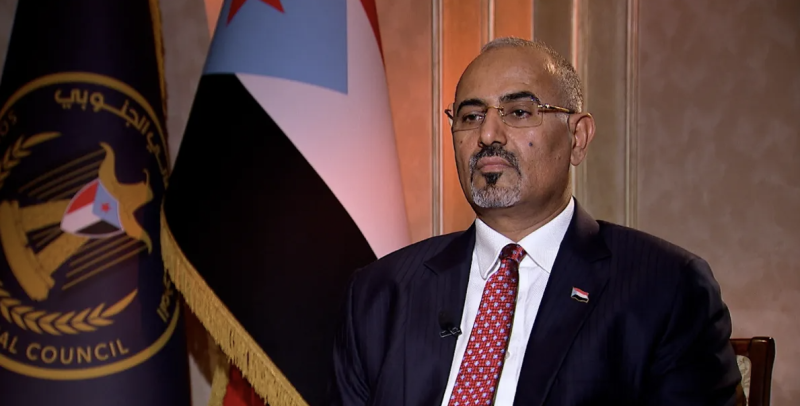

Aden — Yemen’s Presidential Leadership Council members Aidarous al-Zubaidi and Tareq Saleh underscored the need to unify military and p…