African Migrants in Yemen Scapegoated for Coronavirus Outbreak

Migrants say Houthi militia who control northern Yemen are brutally forcing them out of their territory and into dangerous situations.

The Yemeni militiamen rumbled up to the settlement of Al Ghar in the morning, firing their machine guns at the Ethiopian migrants caught in the middle of somebody else’s war. They shouted at the migrants: Take your coronavirus and leave the country, or face death.

Fatima Mohammed’s baby, Naa’if, was screaming. She grabbed him and ran behind her husband as bullets streaked overhead.

“The sound of the bullets was like thunder that wouldn’t stop,” said Kedir Jenni, 30, an Ethiopian waiter who also fled Al Ghar, near the Saudi border in northern Yemen, on that morning in early April. “Men and women get shot next to you, you see them die and move on.”

This scene and others were recounted in phone interviews with a half dozen migrants now in Saudi prisons. Their accounts could not be independently verified, but human rights groups have corroborated similar episodes.

The Houthis, the Iran-backed militia that controls most of northern Yemen, have driven thousands of migrants out of their territory at gunpoint over the past three months, blaming them for spreading the coronavirus, and dumped them in the desert without food or water.

Others were forced to the border with Saudi Arabia, the Houthis’ primary foe, only to be shot at by Saudi border guards and detained in prisons where they were beaten, given little food and forced to sleep on the same floor that they use as a toilet, migrants said in interviews from prison. Some have returned to abusive smugglers, determined to cross the border to find jobs in oil-rich Saudi Arabia.

A Houthi spokesman would not immediately comment on the allegations.

Five years of war between the Houthis and the Saudi-led coalition propping up Yemen’s government have ransacked the country, the poorest in the Middle East, starving and killing its people and smashing the door open to a mounting coronavirus outbreak.

Not only Yemeni civilians are caught in the crossfire. Humanitarian officials and researchers say the African migrant workers who traverse Yemen every year endure torture, rape, extortion, bombs and bullets in their desperation to get to Saudi Arabia. This spring, when the pandemic made them convenient scapegoats for Yemen’s troubles, they lost even that slender hope.

“Covid is just one tragedy inside so many other tragedies that these migrants are facing,” said Afrah Nasser, a Yemen researcher at Human Rights Watch.

More than 100,000 Ethiopians, Somalis and other East Africans board overstuffed smugglers’ boats across the Red Sea or the Gulf of Aden to Yemen every year, according to the United Nations, hoping to make their way north to support their families with jobs as domestic servants, animal herders or laborers in the wealthy Gulf countries whose economies depend on migrants.

The journey is murderous at every stage. At sea, smugglers withhold water and food and throw uncooperative passengers overboard; in Yemen, the migrants are at the mercy of traffickers who torture and sexually abuse them, demanding huge sums of money from their impoverished families to buy their freedom, according to the United Nations, Human Rights Watch and other groups, as well as interviews with migrants.

United Nations surveys show that most migrants do not know about the fighting in Yemen before they arrive, but crossfire and coalition airstrikes find them anyway. At border crossings, Saudi guards shoot and kill them, littering what the migrants call “slaughter valleys” with bodies, migrants and humanitarian officials say. Those who survive are often detained by Saudi authorities and deported.

A Saudi official, who asked not to be named, said allegations of mistreatment of migrants who cross the border illegally are not true and would be an affront to Saudi values.

Since borders clamped shut during the pandemic, the flow of migrants to Yemen has nearly evaporated, plummeting from 18,904 in May 2019 to 1,195 this May, according to the United Nations. But at least 14,500 remain in the country. Many arrived in years past and stayed to scrape together a living or save up before trying to go on to Saudi Arabia.

Ms. Mohammed, 23, said she left Kemise, Ethiopia, after a divorce two years ago, hoping to earn enough as a maid in Saudi Arabia to support her widowed mother and two children back home. The smuggler who brought her to Yemen beat her repeatedly, threatening to kill her unless her family sent money.

When she could not pay, Ms. Mohammed said, she was sold to another smuggler who put her to work at a shisha house in Al Ghar, where the owner forced her to have sex with her customers.

Al Ghar was where she met her current husband. They made a living selling food to other migrants from under a plastic tent. She was making breakfast there when the Houthis arrived.

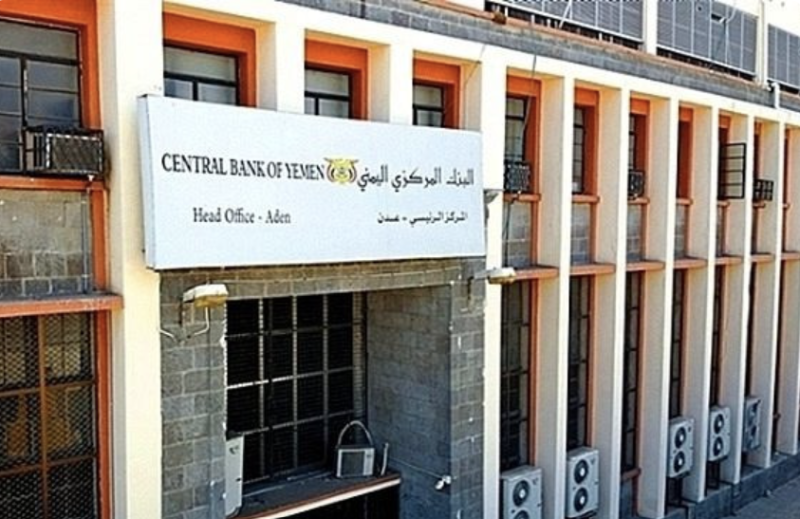

Aden — The United States Ambassador to Yemen underscored the critical importance of safeguarding the independence of the Central Bank of Yeme…

Sana’a – A new international report has confirmed that Houthi militias continue to escalate economic measures against the commercial se…

Aden — For three decades prior to the outbreak of war, Yemen’s oil and natural gas sector played a decisive role in shaping the country…